Find bedding areas now to make your fall season a success

Deer hunters end up in the darnedest places for the darnedest reasons. Some just hunt where they used to hunt. Others rely on tips (from the UPS man to website scuttlebutt). Still others follow the sign (beds, trails, droppings, rubs, scrapes, you name it). It doesn’t really matter how we get where we get, as long as it’s the right place. After all, the three-fold antidote for the Big Buck Blues is location, location, location. But there’s only one reliable way to find the very best spots, and that’s scouting.

This is hardly a revelation, but judging by the feedback I get from the seminar circuit and my website, moonguide.com, it’s clear that few bowhunters know how to scout as well as they know how to shoot their bows. One problem is time. Today’s hectic pace seems to claim every spare minute, which forces hunters to trade scouting time for hunting time. But the real problem, I think, is that we aren’t as proficient at scouting as we could be. While I can’t come up with an extra day to your week, I might be able to help you scout better by scouting smarter.

There are two methods for scouting: with your head and with your feet. In this article, we’ll focus on the first method. Next month, we’ll tackle the subject of fall scouting.

Is It Huntable?

The starting point is answering a trick question: What is the ultimate goal of scouting? Hit this bull’s-eye, and you’re going to save a lot of heartaches and headaches, not to mention legwork. If you answered “find more deer,” you’re only half correct. The complete answer is: locate “huntable” deer. The difference between a spot that’s huntable and one that’s not might be as subtle as the scent of the first drop of rain. But most of the time, it’s as obvious as a broken tooth. You just have to know what to look for.

Some areas are relatively easy to access and straightforward to hunt if you restrict yourself to the right conditions. But the stealth of a diamond thief won’t prevent deer picking you off in many, if not most, areas. I call these spots whitetail moated castles, because they’re essentially impossible to penetrate for two-legged predators. There’s only one solution: leave them alone. The culprits are usually land features that caress and shape the wind and thermals, causing swirling, back-eddying and reversals. Making matters worse, dense, face-slapping limbs and branches prevent a sneaky entry and exit. If those two factors don’t get you, watch out for does bedding between you and the buck you want.

In essence, a buck is huntable if the wind and thermals can be negotiated and if the immediate surroundings can be accessed without disturbing any deer.

Though food sources and some security cover can meet this criteria, the vast majority of the top spots to kill a big buck tend to be situated within the “transition zone” that connects the two. The secret is identifying key micro-features along travel corridors that increase deer traffic. This is precisely what we’re going to look for, and we’re going to be very picky doing it.

Step 1: How to Map Napping Bucks

Knowing where bucks are most likely to bed is central to any scouting system. Like the hub of the spokes of a wheel, all travel patterns revolve around key bedding areas. So let’s start scouting by identifying potential security areas. To do this, we need maps. Thanks to the computer age, you can do most of your field reconnaissance without stepping into the field. Begin with Google’s website, where you’ll find a handy mapping feature that allows you to get the lay of the land (click on the maps function and keep clicking to zoom in).

Once you get a feel for how a potential tract is laid out in relation to human traffic, you’re ready to look at topographic maps to “feel” how key landforms affect its hunt-ability. There are many excellent sources for topos. My favorite is www.mytopo.com (877-587-9004). This site is set up with hunters in mind. They can make custom maps to any size (you can zoom in as far as necessary) with your own boundaries (no more cutting-and-pasting). Contour maps show, to scale, the horizontal positions of contour lines (areas of equal elevation) plus natural and manmade features and true magnetic north. In other words, you can know at a glance how key landforms are orientated – such as if ridges and fields run mostly north-south or east-west.

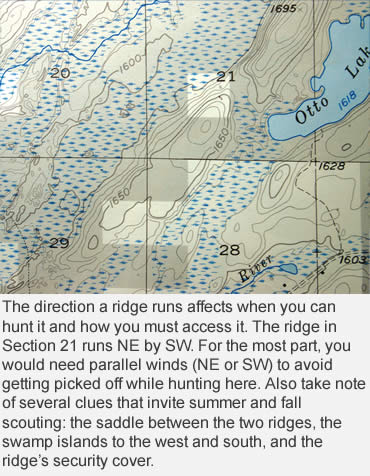

Orientation is a big deal. Either a ridge runs with the wind or against it. In hill country, you must always hunt where the wind blows parallel with the terrain. This provides steady, predictable breezes and thermals. Perpendicular winds and thermals produce erratic back-drafting and swirling. For the most part, I seek out north-south ridges, since the predominate winds where I do most of my bowhunting blow from the northwest in the fall. But El Niño winters of late have taught me the valuable lesson of stockpiling east-west layouts, just in case.

Back to Google. With its handy NAVTEQ technology, you can get a sensory bird’s-eye view of deer heaven by choosing the satellite option in the maps section. (NAVTEQ is a juggernaut in the digital map world, providing clients such as Microsoft, MapQuest, Magellan and Garmin accurate data for automotive and mobile navigation devices.) To tap this service, all you do is place the cursor on the area you want to scout, beginning with the state. Again, keep clicking, and some amazing images will materialize before your eyes. What does satellite photography do that topographic maps don’t? To begin with, these are actual pictures taken by satellite, not a map-maker’s rendition of aerial photos. And since the technology is new, it’s likely to include new roads, trails, clearings and buildings omitted from other base maps. Depending on the area, the degree of detail can be so mind-boggling that you can’t help think about the loss of privacy in our day and age.

Back to Google. With its handy NAVTEQ technology, you can get a sensory bird’s-eye view of deer heaven by choosing the satellite option in the maps section. (NAVTEQ is a juggernaut in the digital map world, providing clients such as Microsoft, MapQuest, Magellan and Garmin accurate data for automotive and mobile navigation devices.) To tap this service, all you do is place the cursor on the area you want to scout, beginning with the state. Again, keep clicking, and some amazing images will materialize before your eyes. What does satellite photography do that topographic maps don’t? To begin with, these are actual pictures taken by satellite, not a map-maker’s rendition of aerial photos. And since the technology is new, it’s likely to include new roads, trails, clearings and buildings omitted from other base maps. Depending on the area, the degree of detail can be so mind-boggling that you can’t help think about the loss of privacy in our day and age.

For mapping bedded bucks, one word sums up what we’re looking for: cover.

Step 2: Connect the Dots

By the time I get to this point, several candidates typically surface that beg further inquiry. Before I analyze vegetative cover, however, I need to plug in water. Most hunters take for granted a deer’s daily need for liquid replenishment. And it’s even more important if droughts continue as they have in recent years. Furthermore, water is synonymous with habitat in arid and semi-arid regions, creating one of the most bowhunter-friendly features: strip cover.

Water comes in many shapes and sizes. Besides obvious lakes, ponds, rivers and streams, don’t overlook springs and sinkholes. These last two have their own unique map symbols worth noting (check the legend of your topo maps). As a general rule, the closer you get to the rut, the more important water becomes in a specific area – both does and bucks seem to settle into key thickets where water is a short stroll away.

Quality whitetail cover comes in mainly three flavors: thick, thicker and thickest. In decent habitat, underbrush along the seams of vegetative breaklines can’t be beat. This is where two or more predominate species – such as conifers and hardwoods – meet to form an observable “edge.” For reasons unknown, deer just seem to congregate along these breaklines, especially after leaf drop. Identifying them with satellite maps is a breeze – conifers appear dark when compared to lighter-appearing hardwoods. Also, if you’re looking for acorns, keep in mind that oak stands have unique globular crowns; other hardwood species are more circular in shape.

Where the habitat is more open and less wooded, be sure to check out brushy draws, fence lines and marshes. The first two are obvious, but marshes can be a real sleeper. Look for “islands” of slightly higher elevation within the swamp, where deer get a reprieve from the muck and ooze and where there might even be some tree cover. Topos usually tattle on these islands. The contours form a simple circle or doughnut (two circles paralleling each other). Satellite images are helpful, too. A change in the color of the vegetation could hint of brushy vegetation, even trees.

I have fond memories of this unique whitetail connection; it produced my first 150-class whitetail from a wetlands refuge in Nebraska. The bucks were bedding in willow thickets that bordered a large impoundment and feeding at food plots planted by the DNR. At first, I tried to make an ambush near the crops, then a ways back. But the trails were too numerous to predict which ones would be the day’s winner. Finally, I back-tracked into the mire, setting up at the convergence of several trails. I barely had enough time to draw my bow in the eye-high sedges, but I made good on the point-blank shot.

In marginal habitat, cover is downright sparse. Deer become opportunists and are forced to make some difficult choices. Ultimately, they make few mistakes. Places such as CRP fields, brush piles – even rock piles – will do in a pinch. A recent telemetry study conducted in New England revealed that isolated dumps and abandoned wood sheds attracted whitetails in suburbia. Translation: Don’t leave any stone unturned in your pursuit of bedded bucks.

Once you’ve mapped potential bedding areas, you’re ready for the final leg of scouting: on your feet (sometimes all fours) in the woods. We’ll deal with that in detail next month. Meanwhile, take these pointers to heart and do your homework now, while there’s still time. It could translate into more time spent hunting when the chase is on.

This article was published in the July 2007 edition of Buckmasters Whitetail Magazine. Join today to have Buckmasters delivered to your home.