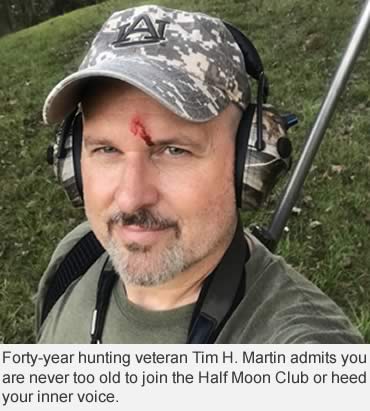

By Tim H. Martin

The lone feral boar rooted in the open field 220 yards away. It was completely unaware of my presence as it swished its tail, seemingly taking pleasure in turning my friend’s pasture in to a crater field. With the winds from the remnants of Hurricane Nate swirling at the back of my neck, I knew I needed to shoot now or risk being smelled.

This would be the eleventh wild hog I’d sniped with my trusty, yet heavy-kicking .300 Win Mag in three days. I’d taken most of the shots from the prone (laying down) position and, as usual, I’d taken care to brace the gun’s butt against my shoulder and square my face to the scope to avoid getting the scope cut magnums are famous for. In fact, I hadn’t taken a ding to the noggin since 1997. (See that story below).

However, I was not comfortable with this particular shot, because I had to lie at an awkward, downhill angle. The butt of the rifle was barely touching my shoulder, my face was turned sharply in order to see through the scope, and a little voice inside my head said, “Timbo, pulling the trigger right now is a bad idea!”

In hindsight, I should have listened and simply taken a few seconds to reposition. But the tusker was broadside, still and offering a perfect side-brain shot. I shrugged off the voice, squinted and squeezed off a shot.

Simultaneously, I saw the pig drop, and stars. You guessed it; the scope bit me good.

As blood trickled from my brow, I laughed at myself, remembering I’d written a Buckmasters Tip of the Week a few years before on this very subject.

Now the inner voice said, “Told ya . . . idiot.”

Since shooting the bobcat and scoping my eye in 1997, I’d taken wildebeest, black bear, zebra, warthogs, several species of antelope, a gaggle of feral hogs and countless whitetails with that rifle, all without incident. Still, I dreaded walking around the Buckmasters office looking like I’d just fought Floyd Mayweather. How embarrassing.

The moral of this story is: You are never too wise and experienced to ignore the little voice inside your head. And, if you don’t take time to brace your rifle properly, you’re never too old to join the Half Moon Club.

Avoid the Half Moon Club (Scope Cuts)

Avoid the Half Moon Club (Scope Cuts)

– By Tim H. Martin

Have you ever noticed how many hunters — even famous ones — have a little scar on one eyebrow or across the bridge of the nose? That’s the telltale sign they’ve been cut by a riflescope.

Whether you call it a scope ding, joining the Half Moon Club or, as they say in South Africa, a Bushveld tattoo, scope cuts are avoidable if hunters learn two easy-to-forget things.

1. Brace that Butt!

The majority of scope cuts occur when the hunter fails to brace the firearm’s butt plate firmly against the shoulder. Usually, this occurs in stands that have shooting rails.

Because the rail does much of the work in propping the gun, it’s easy for a hunter to be complacent about shoulder bracing, especially in the heat of the moment when a deer appears.

When my 10-year-old daughter shot her first deer, it stood only ten yards in front of the shooting rail, requiring a steep, downward angled shot. To compensate, she’d lifted the butt of the rifle high on her shoulder instead of standing up, but I was so intently focused on the deer, I failed to notice the .243 wasn’t against her shoulder.

Even with light recoil, the rifle’s jolt had little to absorb it, and my little girl paid the price with a bruise on the nose. I paid the price later when my wife saw the cut.

2. Square Your Face

Another major contributor in scope cuts is the angle of the face in relation to the scope.

Because not every shot occurs directly in front of the hunter, there are times we have to lean to one side or another to make the shot. This can cause the face to lose its square alignment with the scope; therefore, one corner of the scope is much closer to the face than usual. I accidentally became a member of the Half Moon Club this way in 1997.

While deer hunting from a shooting house in South Texas, a bobcat appeared in a sendero (road-like clearing) to my far left. This shot required me to move, quickly set up in the far-left shooting window, and lean awkwardly across an empty chair.

I whistled to stop the bobcat in the clearing and wasted no time firing my .300 Win Mag. The cat and I hit the ground about the same time.

Had I taken a half-second longer to consciously square my face, it would have saved me a bloody nose, a two-day headache and a scar, not to mention some heavy ribbing from my hunting buddies.

Other factors such as improper scope relief and heaviness of caliber play a part in scope cuts, but if you’ll remember to brace your firearm’s butt plate solidly against your shoulder and square your face to the scope in awkward shooting situations, you’ll enjoy a long career without that popular little scar.

– Photo Courtesy of Tim H. Martin

Read Recent Tip of the Week:

• Buck Whispering: Here’s an unorthodox method of calling deer using Biblical knowledge and faith. Have you ever known anyone who talked wild game into range?